Blog

A Look Inside the Diary of Auguste Morisot

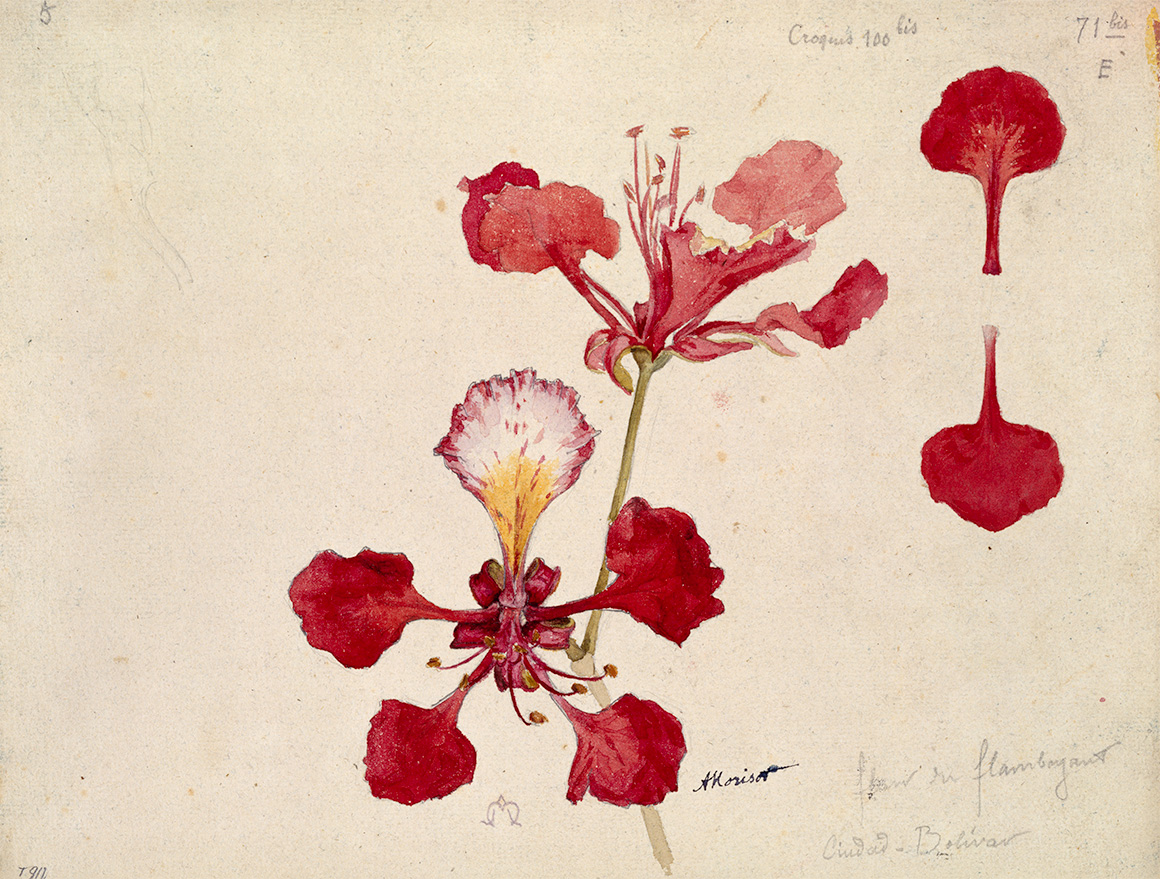

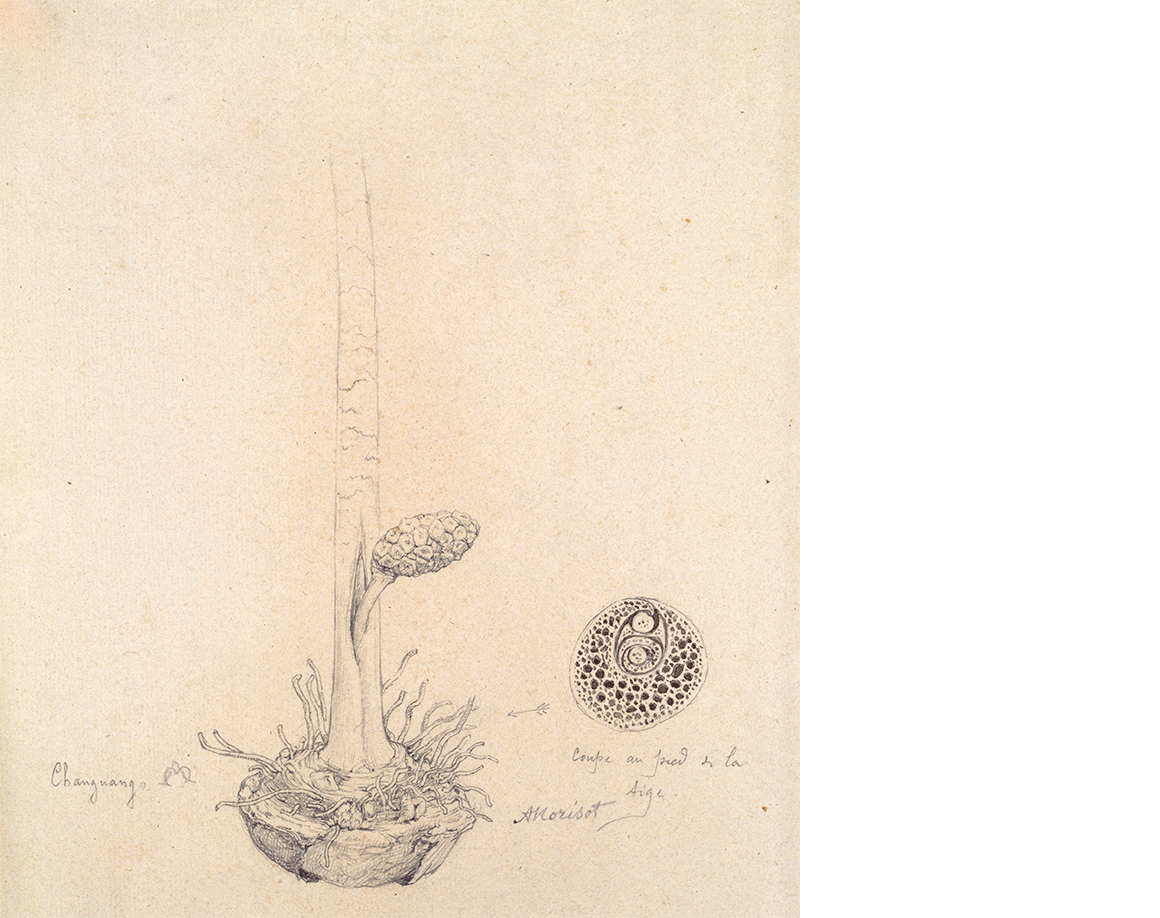

Throughout this trip, which lasted about eight months, Morisot wrote a detailed diary and made a significant number of descriptive pictorial works of the social and ecological reality of that territory. Navigating the Guayana and Amazonas regions, Morisot captured their biological and ecological diversity; the customs and ethnic types of their inhabitants; their human settlements; and economic activity.

In this travel journal, first published by the Fundación Cisneros in 2002 and now available as a PDF on our website, the artist uses his extraordinary powers of observation in inviting us to apprehend in a tangible way the sometimes oppressive experiences of the explorers and the precarious conditions in which they had to work.

Diary of Auguste Morisot, 1886–1887 (excerpts)

We are entirely surrounded. You cannot see more than a kilometer forward or back, so sinuous is this waterway, and each of its successive meanders presents a new surprise, an unexpected silhouette, a more striking impression.

On the banks, here rugged, there flat, are compact masses of vegetation: leaves, plants, vines, branches, all intertwined and confused, forming a veritable wall of greenery where plant life seems to drown out all other life; where the faint morning breeze that just touches us seems to have no access!

This forest, its appearance hostile, impenetrable, as if closed to every human being, is so beautiful in its grandeur, so calm in its imposing majesty, that I feel immediately overcome by its wonderful attractions. Yes, I filled my eyes and my heart with this magnificent nature, and in spite of the need to launch exclamations at every turn of the Bolívar’s wheel, I remain silent. Otherwise, such spectacles left my partner cold, since he has seen them before, and also does not see them from the same point of view. With you, my friends, I would have liked to share my impressions. How nice it would be to see these beauties together! My emotions would increase a hundred-fold! From time to time, some banks appear bare, sandy. Animals, seen resting, are stationed in the sand; some capybaras surprised in their quietude slowly disappear under rifle fire from some passengers. Some jabirus, great white herons with a red collar, also called garzones soldados, erect their tall stature stand at the foot of the leafy wall like vigilant sentinels. They are also the object of some gunshots, without being affected. (Excerpt from page 126, April 6)

Today it is essentially a mercantile center, with about twelve thousand inhabitants. There isn’t any industry; but they are occupied with gold mining, commerce, and trade. The only means of transportation of imported goods and export products are steamboats and sailing ships going up the Orinoco to Bolívar. They import all kinds of groceries, objects, and industrial products from all countries, which trade houses sell at fabulous prices to residents and traders from the Orinoco and Río Negro. These traders, adventurous merchants, are the intermediaries between the producers and trading houses. They travel up the river in large boats loaded with food and objects of all kinds for exchange. They stop to provision the river towns and even go to the interior to peddle their wares in competition with the country's products: cocoa, vanilla, Tonka beans or sarrapia, sugar cane, rubber, gums of many kinds, buying or exchanging with the natives at despicably low prices. They then take those products to the city merchants, who, without any work, deliver them for consumption and export at great profit. At this point the Orinoco is very low, it is the end of the summer or dry season. Soon the rainy or winter season will begin. Then the river swells prodigiously. Its level rises ten to fifteen meters and its waters sometimes reach the first houses of Bolívar, about twenty meters from its current level. Can you imagine the mass of water that must fall within the six rainy months? Beyond the flooded plains Bolívar a true inland sea is formed. (Excerpt from page 138, April 9)

The night of Maundy Thursday a real storm swept over our roof. It was impossible to protect the lamp against the gusts of wind. We had to relight it several times.

Beneath the inky night outside, its flickering flame drew in intermittent, shifting light the hammocks, rifles, helmets and different objects hanging from the posts and beams. Suddenly, dazzling lightning burned the night with a loud crash and vigorously highlighted those same objects as black silhouettes against a fiery sky.

All night long, our hammock was rocked by a furious wind wet with rain that pummeled us.

Completely wrapped in my blanket, it did not bother me too much. (Excerpt from page 155, April 19–24)

To come to the city, the women equip themselves with a great red shirt/skirt, lifted before them by their prominent bellies. The voluminous clothing hangs, loose, with a pleated straight line falling from the armpits, with short sleeves, and a kind of wide neck with folds covering the shoulders. The lower part of the clothing is adorned with frilly yellow, blue, and green bands. A varicolored handkerchief is knotted graciously on the head, partly falling freely over the shoulders. Color is much sought after by women. I prefer the navy blue worn by the men.

Some Caribs live here permanently. One day, a Carib who came to the restaurant with his wife, carrying coal (as they are carboneros), agreed to take the time to pose for a sketch. These Indians are easy going, speak Spanish pretty well, and are more or less the only ones who have sought contact with civilization. We will soon see others even more typical, in their own environment, who unlike these have not suffered change. (Excerpt from page 186, May 24)

Two good hours riding. Delightful ride through the same plains as yesterday, the same savannahs strewn with rocks and chaparral. The hill of the Dead is coming into focus more than a kilometer to our right.

We go around hills and one round rock; some of these small mountains are completely bare on one side and covered on another with a semblance of jungle.

Here and there, more or less cylindrical rocks; marked by very deep, equidistant holes, giving them the appearance of gear wheels. After crossing the inviting waters of several clear morichales, shaded by groups of majestic Moriches palms (palms that are taller and more spindly than those in Santa Rita, but with short palm fronds), the rocky mass of the Pintado hill stands erect before us. A mountain of a single block of granite that rises perpendicularly to over a hundred meters above the surrounding trees.

Except for some gullies where bushes grow, this edge is smooth, bare, and on this broad vertical plane are colossal, peculiar inscriptions, well proportioned and decorated with an impression and amazing for its audacity and workmanship. When they speak of Cerro Pintado, the Indians claim that their ancestors arrived in curiaras at the tip of this granite block, when the waters covered all the plains and had not yet formed the bed of the Orinoco.

Inscriptions on this granite mountain would go back, then, according to their beliefs, several thousand years...perhaps before the sinking of the legendary Atlantis?

While Chaffanjon looks for an accessible place to reach the top of the hill he wants to explore, I carefully draw the inscriptions: a snake of at least a hundred meters long flows in waves all along the flat surface, a large lizard or alligator runs over, a huge centipede, a little man, a bird (gallina), a kind of multi-footed table in which there are concentric circles, like food dishes perhaps, and concentric rectangles and ovals. (Excerpt from page 284, September 25)

His portrait was almost finished when, suddenly, one of his companions burst into the ranch; some words in the Indian language made him jump up and run out with him. I was left with my brushes in the air.

The whole town is upset. We learned that the comrades of my indian model want to kill us. Why? It is a treacherous blow from the merchants. In the hope of not paying the porters and to distract them from their rights, Raimundo Mobna and Castel deemed it very clever to agitate against us, especially against me, asserting that we had performed witchcraft, that Popurito was under my influence and that misfortune would ensue.

Indeed, the misfortune that awaited them was being abused by these hucksters in the form of payment.

But the Indians are not satisfied with this coin, and if a moment before it was a question of killing us, now thanks to the intervention of a civilized Guahibo indian captain who lives with his family on the ranch next to ours, it is the turn of the merchants to fear their anger. This captain speaks very good Spanish. Chaffanjon spoke with him all morning, asking him about the customs and life of the Guahibos.

It was he who served as our interpreter and convinced his compatriots to pose for the photographic apparatus and for me. Made aware of the facts, it did not take much to put things in place, and the peddlers had to pay, not without a rain of insults and violence against two of these unfortunate Indians.

To put the incident behind us, Captain Cordero gave a ball at home. Needless to say, instead of attending in honor, the merchants were excluded. Our Baniva sailors were included in the party. Although the Indian element dominated, the dancing is more Venezuelan than Indian. The few women from the village were there in all their finery; white blouse and white ruffled skirt.

At the sound of the cuatra, the maraca and singing, some couples link arms; but as women are in the minority, pairs of the indian men dance together. Others drink guarapo, fermented liquor, eat cornbread and smoke until the inside of the ranch is a cloud. We didn’t stay long.

Captain Cordero is fully adapted to the level of civilization of the villagers; and even has risen above them, since his ranch is the best kept, the most comfortable, and the best organized of all and he also knows Spanish, while the others can barely speak. (Excerpt from page 291, October 10)

Top Image: Auguste Morisot, My Desk Pad (June 1886). Black ink wash with pen strokes, white goauache on paper, 7 ½ x 9 ½ in (18.9 x 24 cm).